Traumatic past experiences can haunt the present as ghosts. It is no surprise, thus, that many Holocaust-related fictions have reworked a mythological figure from the Jewish folklore: the dybbuk, a malevolent wandering spirit that takes possession of the body of a living being in order to fulfill his unfinished tasks. In the Mossad file on Adolf Eichmann, shown recently at an exhibit in Tel Aviv, the Nazi criminal was code-named dybbuk.

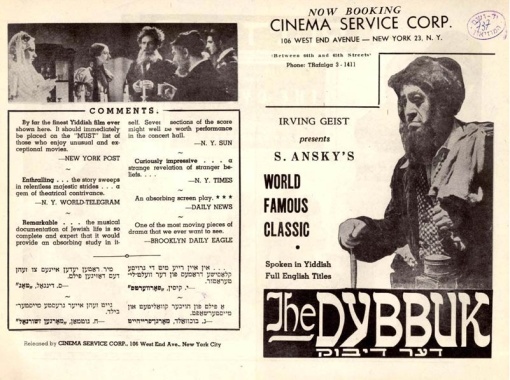

This legendary figure gained popularity in the first decades of 1900 after the play The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds (1914) by Russian Jewish playwright S. Ansky and the Polish fantasy film The Dybbuk, based on the play and directed by Michał Waszyński in 1937.

As a post-Holocaust theme, the dybbuk has been used both in a comic key and in a horror register.

1. Genghis Cohn

The Dance of Genghis Cohn (1967) by French novelist Romain Gary features a former SS officer, commander Schatz, haunted by the dybbuk of a Jewish ventriloquist he had sent to death in the camps with a public execution. In 1993 Elijah Moshinsky made a tv-film adapted from Gary’s novel, Genghis Cohn. The comedian’s ghost does his best to cause his “host” the most awkward and embarassing misadventures.

The film can be watched on YouTube.

2. The Entertainer and the Dybbuk

The Entertainer and the Dybbuk is a 2007 short novel by Sid Fleischman, renowned author of children’s books. It tells the story of Freddie, an American soldier who has stayed in Europe after the war to work as a ventriloquist. One day Freddie finds in his closet the ghost of a twelve-year-old boy killed in the Holocaust. The boy, Avrom, asks Freddie if he can inhabit him during his shows, and uses this opportunity as a way to find in the audiences the SS officer who shot him and his sister.

3. The Unborn

The Unborn is a 2009 horror film directed by David S. Goyer. Sofi Kozma and her twin brother Barto, at Auschwitz, were subjected to the experiments of Doctor Josef Mengele. Many years later a young woman, Casey (we eventually learn she is Sofi’s granddaughter), begins to have strange hallucinations and her eye color shifts from brown to blue. Barto, as it turns out, died during a Nazi experiment to change his eye color, and awoke from the dead in the form of a dybbuk. Sofi’s unresolved past is the cause of his perpetuation. The key issue of the film, according to Aaron Kerner, is

(…) how one generation might haunt the proceeding generations. Goyer’s film then might function as a literalized manifestation of second or third generation survivors riddled with “survivor guilt”. The weight of the Holocaust, even when survivors elect not to speak about it (perhaps because they don’t want to burden anybody with their traumatic memories), can be enormous and return to the succeeding generations as an uncanny specter, manifesting in forms of (survivor) guilt or melancholia. (Film and the Holocaust, p. 160).