Source: Jodi Rudoren, The New York Times, January 26, 2014

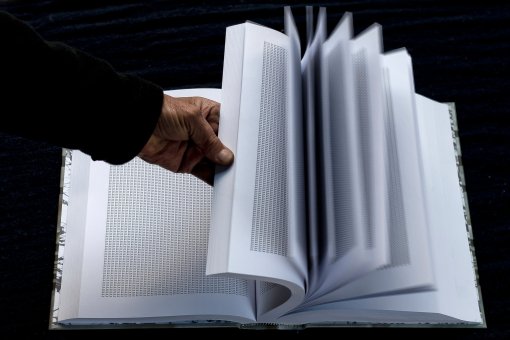

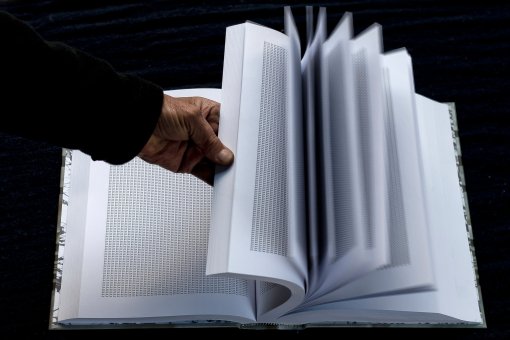

There is no plot to speak of, and the characters are woefully undeveloped. On the upside, it can be a quick read — especially considering its 1,250 pages.

The book, more art than literature, consists of the single word “Jew,” in tiny type, printed six million times to signify the number of Jews killed during the Holocaust. It is meant as a kind of coffee-table monument of memory, a conversation starter and thought provoker.

“When you look at this at a distance, you can’t tell whether it’s upside down or right side up, you can’t tell what’s here; it looks like a pattern,” said Phil Chernofsky, the author, though that term may be something of a stretch. “That’s how the Nazis viewed their victims: These are not individuals, these are not people, these are just a mass we have to exterminate.

“Now get closer, put on your reading glasses, and pick a ‘Jew,’ ” Mr. Chernofsky continued. “That Jew could be you. Next to him is your brother. Oh, look, your uncles and aunts and cousins and your whole extended family. A row, a line, those are your classmates. Now you get lost in a kind of meditative state where you look at one word, ‘Jew,’ you look at one Jew, you focus on it and then your mind starts to go because who is he, where did he live, what did he want to do when he grew up?”

The concept is not entirely original. More than a decade ago, eighth graders in a small Tennessee town set out to collect six million paper clips, as chronicled in a 2004 documentary. The anonymity of victims and the scale of the destruction is also expressed in the seemingly endless piles of shoes and eyeglasses on exhibit at former death camps in Eastern Europe.

Now Gefen Publishing, a Jerusalem company, imagines this book, titled“And Every Single One Was Someone,” making a similar statement in every church and synagogue, school and library.

While many Jewish leaders in the United States have embraced the book, some Holocaust educators consider it a gimmick. It takes the opposite tack of a multimillion-dollar effort over many years by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial and museum here, that has so far documented the identities of 4.3 million Jewish victims. These fill the monumental “Book of Names,” 6 1/2 feet tall and 46 feet in circumference, which was unveiled last summer at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“We have no doubt that this is the right way to deal with the issue,” said Avner Shalev, Yad Vashem’s director. “We understand that human life, human beings, individuals are at the center of our research and education. This is the reason we are investing so much in trying to retrieve every single human being, his name, and details about his life.”

Mr. Shalev declined to address the new book directly, but said dismissively, “Every year we have 6,000 books published about the Shoah,” using the Hebrew term for the Holocaust.

The book’s backers do not deny its gimmickry — Mr. Chernofsky used the Yiddish word “shtick” — but see it as a powerful one.

Ilan Greenfield, Gefen’s chief executive, noted that there is a blank line on the title page where people can dedicate each book, perhaps to a survivor like his mother-in-law.“Almost everyone who looks at the book cannot stop flipping the pages,” he said. “Even after they’ve looked at 10 pages and they know they’re only going to see the same word, they keep flipping.”

The Gefen catalog lists the book for $60, but Mr. Greenfield said individual copies would probably sell for closer to $90 (buy 1,000 copies and it is $36 each). Since the book went on the market a few months ago, he said, 5,000 have been printed. One person bought 100 to distribute to the offices of United States senators, and Jewish leaders in Australia and South Africa, Los Angeles and Denver, have bought batches for their communities.

Abraham H. Foxman, national director of the Anti-Defamation League, enlisted three donors to buy 1,000 each and is giving them away: He wants one in the Oval Office and, eventually, on every Passover Seder table. “When he brought me this book I said, ‘Wow, wow, it makes it so real,’ ” said Mr. Foxman, himself a Holocaust survivor. “It’s haunting.”

The idea began in the late 1970s at the Yeshiva of Central Queens in Kew Gardens Hills, where Mr. Chernofsky taught math, science and Jewish studies and, one year, was put in charge of the bulletin board for Holocaust Remembrance Day.

“I gave them blank paper, and I said, no talking for the next 30 minutes — that was a pleasure,” recalled Mr. Chernofsky, 65, who grew up in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and moved to Israel 32 years ago. “I said, ‘I want you to write the word Jew as many times as you can, no margins, just pack them in, just take another paper and another paper until I say stop.’

“We added up the whole class,” he added. “It was 40,000 — nothing.”

Years later, Mr. Chernofsky printed out pages filled with “Jew” six million times and put them in a loose-leaf notebook, which he showed visitors to his messy office here at the Orthodox Union, where he is the educational director. His uncle took the notebook to a Jerusalem book fair, where a bookbinder saw it, and made a limited edition. Mr. Greenfield eventually came across a copy and approached Mr. Chernofsky about 18 months ago with the idea of mass production.

Each page has 40 columns of 120 lines — 4,800 “Jews.” The font is Minion; the size, 5.5 point. The book weighs 7.3 pounds.

Its titleless cover depicts a Jewish prayer shawl, sometimes used to wrap bodies for burial. Mr. Chernofsky said it was Gefen’s choice; he would have preferred solid black, or a yellow star like those the Nazis made Jews wear.

An Orthodox Jew with nine grandchildren, Mr. Chernofsky is a numbers man, the kind of person who cannot climb stairs without counting them (41 up to his apartment). “Torah Tidbits,” the publication he has edited for two decades, always lists the number of sentences in the week’s Torah portion (118 in last week’s “Statutes”).

He likes to play with calendars, and is tickled that for the next three months, the Hebrew and English dates match: Feb. 1 is the first of Adar, April 30 the 30th of Nissan.

Mr. Greenfield, the publisher, said his goal was eventually to print six million copies of “And Every Single One Was Someone.” With each copy 2.76 inches wide, that would fill 261 miles of bookshelves — just shy of Israel’s 263-mile north-south span. (And net Mr. Chernofsky, at his contracted rate of $1.80 per book, $10.8 million.)

“Harry Potter, in seven volumes, used 1.1 million words,” noted Mr. Chernofsky, a devotee who has a Quidditch broom hanging in his office. “This has six million in it, so I outdid J. K. Rowling.”

![]()

![]() to the Holocaust, managed to escape on foot from Warsaw to Russia at the outset of World War II. Once he relocated to the Soviet Union, his troubles continued. Although he composed prolifically, many works were banned because of Stalinist anti-Semitism. He died in 1996, 10 years before “The Passenger” first saw the light of day, at a concert performance in Moscow. Read the full article.

to the Holocaust, managed to escape on foot from Warsaw to Russia at the outset of World War II. Once he relocated to the Soviet Union, his troubles continued. Although he composed prolifically, many works were banned because of Stalinist anti-Semitism. He died in 1996, 10 years before “The Passenger” first saw the light of day, at a concert performance in Moscow. Read the full article.